DON'T FEAR THE ZOMBIE: the black plight of the reanimated corpse

where I try to make sense of consciousness through Haitian Vodou, Fela Kuti, classic horror, and Tyler, The Creator's newest album, CHROMAKOPIA

There is an inherent gore to the zombies we know of today.

Gaunt, greying carcasses with rotting sunken sacks where an eyeball should be. Teeth decaying into worn gums. Maggots and flies spilling from a cerebrum gone to mush beneath a chipped skull. Limbs partially severed, swinging forward as a body adorned in torn clothes (reminiscent of a life once lived and a struggle to revive) stumbles towards living bodies; other bodies with warm blood running red and a beating heart and a brain.

Something more sinister lies at the root of its terror, however. These zombies still look like you or me, but something is just… slightly off. Something you can’t quite place or recognize.

In Sigmund Freud’s 1919 book The Uncanny, Freud posits that the uncanny is “that class of the terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar.” He traces uncanny’s etymological roots to the German word unheimlich. He provides several understandings of the word heimlich, which can be distilled into two camps: (1) “familiar,” “belonging to the home,” “comfortable,” “intimate” and (2) “concealed,” “kept from sight,” “secret” [1]. Thus, unheimlich becomes what is unfamiliar, does not belong to the home, is not comfortable, as well as something no longer concealed, something revealed and uncovered. This provides an almost paradoxical understanding of the uncanny — the uncanny is both what is unknown and what is now known.

Are you feeling unsettled yet?

From this, we can conclude that what is uncanny is not simply a pure unknown, but rather a return to a knowledge that has been repressed. Something (or someone) we once figured a stranger is now recognized as closer to us than we initially believed. Are you feeling unsettled yet?

Freud centers the concept of “the double” in the uncanny. The double exists as a “preservation against extinction,” with the immortal soul being the first “double” of the body, per Freud’s recounting of fellow psychoanalyst Otto Rank’s discussion on doubles [1]. The double in the mirror, in your shadows, in your dreams, in your spirits are a reflection of one’s past and one’s future. There is a part of ourselves, often in childhood (it’s always childhood with Freud), unrestrained by circumstance and earthly fears. We can dare to dream for another self, and we preserve these selves in our doubles. As time goes on, these doubles are reduced to a fantasy that can only cling to the back of our minds. They are no longer a fantastical clutching onto immortality, but a signal of our incoming death and what we have not become. The death of lives that could have been. The uncanny evokes the repression of what was once known to us, what has been locked away in a double separate from ourselves. Are you feeling unsettled yet?

Zombies prompt us to look within ourselves.

Sure, getting bitten by a zombie would hurt. Like a lot. But zombies do not possess thought; they cannot strategize, they have no concept of emotional or psychological human workings, their only internal directive is to feed — or so we believe. Then, we arrive at: how will humans respond to the zombie? Who is the real danger?

The struggle to survive in zombie media stirs anxieties within us. Who can be trusted to defend against these zombies? How will I know who is a zombie when they can look like me and look like you? These beings are refused peace in death, rendered catatonic hollow husks of a human, reduced to something unthinking, unfeeling, unknowing, unremembering, cursed to feed forever and proliferate infection as they mindlessly chase something. More on that later.

They look like you and me. We can become one of them, you and me. You and me, we fear what we can’t understand. We fear we will become what we can’t understand. We fear we will lose the ability to understand and to be understood. We fear we have already lost, unknowingly.

Are you feeling unsettled?

The modern western zombie has its origins in West Central Africa. The Bantu and Bakongo tribes along the Congo river believe in the deity Nzambi. Those considered “sorcerers” or “dark priests” practiced creating zumbi, or “bottle fetishes,” where a person’s soul is trapped in a bottle and the soulless entity is stripped of agency and forced to serve the sorcerer [2].

The concept of “Nzambi” and “zumbi” was transported to Haiti during the transatlantic slave trade, and the “zombi” (also spelled zonbi in Creole) emerged in Haitian Vodou.

Haitian slaves believed in two parts of the soul, a double inside: gros-bon-ange (big guardian angel) which represents one’s individual life force and ti-bon-ange (little guardian angel) which represents one’s knowledge, experience, and personality. They believed that when they died, their gros-bon-ange, their individual life force, would return to lan guinée, a heavenly afterlife where they could be free. If a proper death ritual is not fully conducted, however, then one’s gros-bon-ange could become trapped on earth [3]. This plants the seeds of a focus on respecting and honoring the dead.

Baron Samedi is a “lwa” or spirit in Haitian Vodou who guides the souls between the living and the dead. If one offended Baron Samedi or took their own life, it was believed that he would turn them into a zombi as an undead laborer. Zombis were to work tirelessly and unthinkingly, without autonomy, and without a memory of who they were before zombification. Some say a zombi can only speak again if given salt [9]. “Bokors,” or sorcerers, served lwas and acted as earthly forces that perpetuated the zombi. Bokors could be fellow enslaved Haitians, often in overseer positions, and would use these threats of zombification to subjugate fellow slaves into enduring suffering and not committing suicide as a means to escape it [4]. The fear of zombification reflected enslaved Haitians’ fear of eternal servitude and loss of autonomy.

In Zombified and Traumatized: Healing in Black Women’s Zombie Literature, Mikayla Johnson argues that through revolution, the zombie embodies both confinement and liberation. Johnson discusses a religious ceremony where enslaved Haitians drank a black pig’s blood and took its bristles for strength and unity following slave rebellion, as recorded in Histoire de la Revolution de Saint-Domingue (1814) by Bois Caiman Vaudou. Johnson highlights how this type of imagery mirrors Hollywood’s depiction of inhuman monsters unleashing terror on the civilized, a common white-centric recollection of the Haitian Revolution. Among white westerners, the zombie became distilled into directionless workers incapable of complex thought and easily defeated by white protagonists, were a revolt to occur [2].

These attitudes are further reflected in the words of Robert Lansing, the US Secretary of State from 1915 to 1920 at the dawn of the United States’ occupation of Haiti; Lansing has said: “The experience of … Haiti show(s) that the African race are devoid of any capacity for political organization and lack genius for government. Unquestionably there is in them an inherent tendency to revert to savagery and to cast aside the shackles of civilization which are irksome to their physical nature [5].” The cultural significance of the zombi in Haiti furthered imperialist powers' desire to quell and control Haitians, thought to be uncivilized people driven by an animalistic instinct to destroy. This depiction continued to taint Western understanding of zombies.

Occultist, explorer, and participant in cannibalism William Seabrook released bestselling book The Magic Island in 1929, where he discusses his time in Haiti and ultimately exposes the United States to the Haitian zombie (and popularizes the spelling of zombie over zombi). Seabrook wields racist language in his rumination on Haitian zombies, describing them as lacking intelligence and not feeling pain the same as the living (or Europeans) [6].

Seabrook recounts his introduction to zombies at the Haitian American Sugar Company: “The supposed zombies continued dumbly at work. They were plodding like brutes, like automatons. The eyes were the worst. … They were in truth like the eyes of a dead man, not blind but staring, unfocused, unseeing… It was vacant as if there was nothing behind it.” Seabrook sensationalized these zombie encounters, refusing to interrogate the conditions of these workers — slaves employed by American manufacturers working 18-hour shifts in filthy conditions [7].

In 1932, the first zombie film White Zombie was released, largely inspired by Seabrook’s 1929 book. Bela Lugosi stars as white Haitian Vodou master Murder Legendre who runs a sugarcane mill operated by zombies. Madeleine Short arrives in Haiti with plans to get married to her fiancé Neil Parker. However, plantation owner Charles Beaumont falls in love with her and enlists Murder to zombify her. With the help of missionary Dr. Bruner, the white couple finishes the film as humans, and the Vodou master and his zombies fall off a cliff to their death. Ultimately, the white, Christian, Western protagonists are under attack by the “uncivilized” black magic — black magic — of Haiti and need to overcome it.

Writer and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston details her own experiences and learnings of zombies in her 1939 book Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica. She writes of how families employ various precautions to protect a dead one’s body from disturbance and zombification. Some set up 36-hour (the time frame where revival of a body is possible) cemetery watches post-burial. Some cut the bodies of loved ones open to insure a real death. Peasants place a knife in the right hand of the corpse and prop the arm so it slashes anyone who dares to disturb the body on its first day in the ground. Most popular, however, is to poison the body.

Hurston notes that upper class Haitians, while maintaining a fear of zombies and participating in safeguarding preparations for the dead, do not outwardly mull over zombies like the poor. They would tell Hurston that the commonpeople are superstitious and zombies are just a myth. Hurston suggests that the upper class couldn’t bear to fathom a reality where, despite being “loved to [their] last breath by family and friends, [they must] contemplate the probability of [their] resurrected body being dragged from the vault … set to toiling ceaselessly in the banana fields, working like a beast, unclothed like a beast.” The upper class did not want to face a reality where they were stripped of their status and intelligence and reduced to something unthinking and unknowing. In a zombie, they were faced with a terrifying alternate self.

Hurston recalls encountering a zombie, which she describes as “a broken remnant, relic, or refuse of Felicia-Felix Mentor … I listened to the broken noises in its throat, and then, I did what no one else had ever done, I photographed it [8].” I find myself stuck on this word of “refuse.” Yes, there is the meaning of unwanted and discarded waste, which already has bleak implications for describing a human, dead or not. But I also see a refusal, whether a refusal to be truly living or a refusal to stay dead. Such is the oxymoronic living dead.

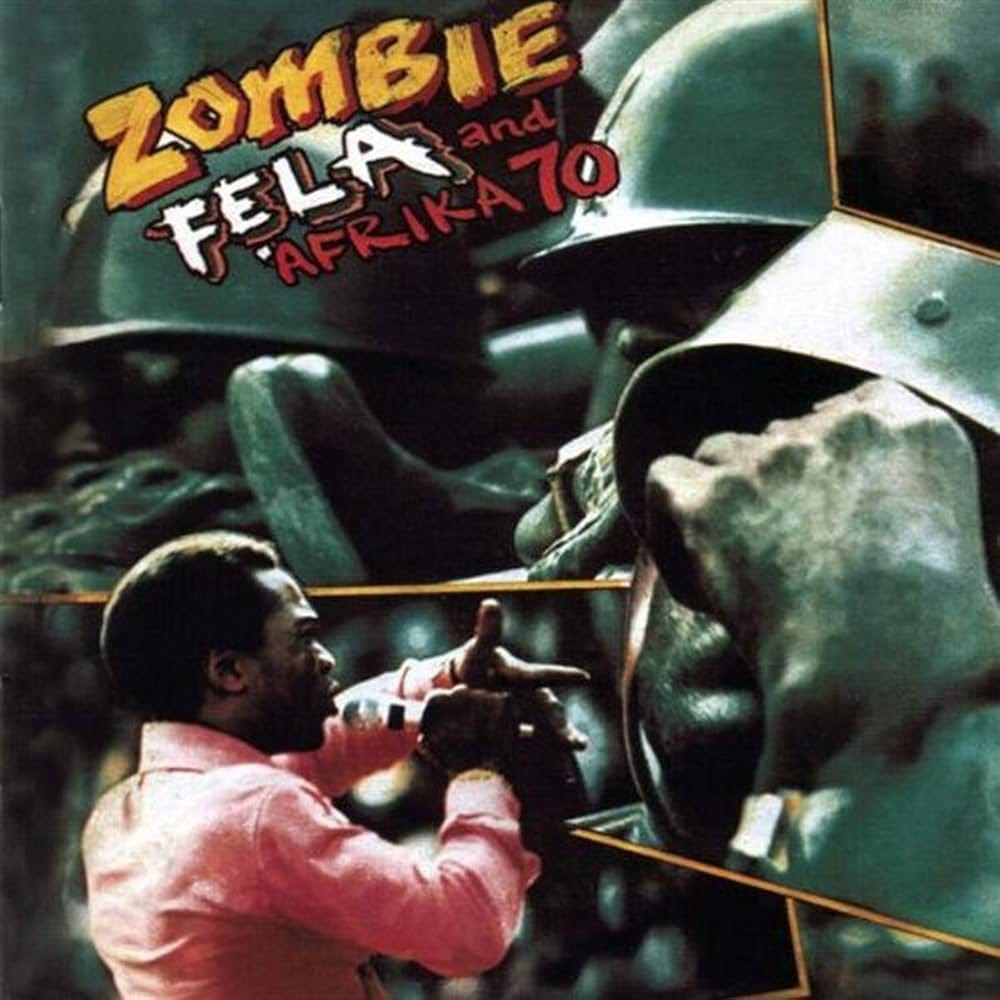

My first real introduction to the zombie was through Nigerian musician Fela Kuti’s song “Zombie.” My dad possessed an extensive CD collection when I was a kid — I’m talking bookshelves on bookshelves in the living room, wheelable carts for easy transportation, no closet kept safe from a stray CD, and a rotation in the glove compartment of his car. The works of Fela Kuti often found a seat in that glove compartment. I don’t remember how old I was when I first heard Zombie (I couldn’t have been older than six when I would ask for him to play Fela on the way to our weekly library visit), but I remember being entranced by Fela’s spirited brass and frantic percussion.

Fela Aníkúlápó Kuti (Aníkúlápó a name chosen by Kuti himself to reject his “slave name,” Ransom; it means “one who carries death in their pouch,” which Kuti cites for why the Nigerian government “could never kill him”) is widely regarded as the creator of afrobeat, blending funk, Black American and Afro-Cuban jazz, calypso, highlife, and traditional Yoruba music. He was born to activist parents. His father Israel Oludotun Ransome-Kuti was a preacher, teacher, and founding president of Nigeria Union of Teachers, and his mother Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti was a teacher, women’s rights activist, and founder of the Abeokuta Women's Union [9]. In 1969, a 30 year old Fela traveled with his band Afrika 70 to the United States. There, he became inspired by the African American Civil Rights Movement and particularly inspired by the words of Malcolm X. He returned to Nigeria in the wake of the Biafran War, compelled to spur political movement through music and to devote himself to pan-African, anti-capitalist rebellion [10].

In 1976, Fela released “Zombie.” The cover art features Fela, microphone in hand, facing army personnel. Fela breaks a vibrant trumpet solo to sing, “Zombie no go go, unless you tell am to go / Zombie no go stop, unless you tell am to stop / Zombie no go turn, unless you tell am to turn / Zombie no go think, unless you tell am to think.” A chorus chants a steady “zombie” and “zombie o, zombie” in the background. He then proceeds into indignant incantation: “Go and kill! / Go and die! / Go and quench! / Put am for reverse!” It finishes with defiant military commands: “Quick march! / Slow march! / Left turn! Right turn! About turn!”

The funky track is regarded a scathing diss to the state-sanctioned violence via Nigeria’s military dictatorship. Fela mocks the zombies’ thoughtless following of commands, getting pulled in every direction — quick, slow, left, right — and only moving once told to move. Only thinking once told to think. “Put am for reverse!” likens the zombies to machines without direction of their own, meant to fall backwards into a world they cannot anticipate. Fela’s political activism had already put the musician at odds with the Nigerian government, and this song and its growing popularity furthered the friction.

On February 18th, 1977, one-thousand Nigerian soldiers surrounded Fela Kuti’s communal compound, Kalakuta Republic. Fela shared Kalakuta Republic with family, friends, lovers, bandmates, allies, and anyone willing to share the spirit of rebellion and music. During the 15 hour siege, the army severely beat, assaulted, raped, and sexually mutilated the people in the compound. Fela’s mother, Funmilayo, was thrown out of a window, sustaining injuries that would eventually lead to her death months later. Kalakuta Republic was set on fire [10].

“Zombie” undoubtedly rebukes Nigeria’s military, and the army’s response shows they felt the dagger. However, in When the Zombie Becomes Critic: Misinterpreting Fela’s “Zombie” and the Need to Reexamine His Prevailing Motifs, Phillip Effiong argues that the meaning of “Zombie” can be stretched further.

Rather than limiting the scathing lyrical condemnation towards just the military, Effiong suggests the song decries all “complicity and docility in the face of subjugation.” Effiong cites Fela’s various castigations of exploitation and oppression in all forms, including but not limited to the military [11]. Fela attributes power to musicianship in the potential for rebellion among all people. Zombification exists not just in those mindlessly wielding weapons, but those passive in silent acquiescence when confronted with tragedy.

In “Dead or Alive: Parables from Black Zombie Media,” Kettering Waddell writes, “We may be awakened to the plight of our existence, but that isn’t subversive enough to enact the change that will protect our peace and sanity. Even in our dreams, we are subjected to the reminder that we exist in a world where none of us are safe, dead or alive [12].” Ultimately, we are all haunted and it’s our collective duty to resist this haunting — resist becoming unfeeling and unthinking in a cruel system that thrives on our complacency. This is Fela Kuti’s “Zombie.”

George A. Romero’s 1968 Night of the Living Dead is the blueprint for the modern zombie film. It was the first film to depict a zombie apocalypse with droves of flesh-eating zombies rather than individual zombie events — and it was a hit. The film never explicitly uses the word “zombie,” but its supernatural antagonists are corpses that have come back to life, thus aligning with the modern understanding of zombie.

The film begins with young white woman Barbra and her brother Johnny visiting their father’s grave. They’re bickering: Johnny doesn’t believe in the futility of honoring a man that he can’t even remember the looks of, while Barbra in earnest wishes to pay respects to her father.

A man dressed in a slightly tattered suit and permanent grimace approaches them with a jilted walk. Only Johnny possesses a sense of urgency regarding the odd man —until the gangly figure lurches towards Barbra and attempts to bite her. Johnny fights back and is killed by the man, meanwhile Barbra is able escapes to a farmhouse where the owner’s flash has already been mangled by zombies.

This man, and the other zombies in this film, are not explicitly ghoulish. They don’t have lacerated, misshapen faces or decaying, odd-colored teeth. They look eerily similar to humans.

Psychiatrist Ernst Jentsch believes that one of the most successful ways to evoke the uncanny is to balance the uncertainty of whether a figure is a human being or an “automaton.” However, the viewer’s attention must not be so focused on uncertainty that they are compelled to quash the uncertainty, consequently dissipating the peculiar emotions arisen [1]. The zombies of Night of the Living Dead build tension through this delicate balance.

After Barbra escapes to the farmhouse, she is in a catatonic daze, unable to do or say much except think of the brother she has lost. She encounters Ben, a black man who then assumes the protagonist role. The pair eventually meet five other (white) folks in the house: young couple Tom and Judy, and disgruntled couple Harry and Helen with their daughter Karen. Ben, played by Duane Jones, becomes the voice of reason amongst the survivors in the house: he finds the radio and television which are crucial in updating live information, discovers the zombies’ aversion to fire, and devises the plans to secure the house, attack the zombies, and get survivors to the rescue center.

However, the other survivors pose more of a threat to him than the zombies.

There’s Tom and Judy, well-meaning if not bumbling at times (see: Tom accidentally setting the escape truck on ablaze and Judy running after him despite being told to stay in the house and boom now they’re both stupid and on fire). Barbra spends the duration of the film oscillating between hysterical & useless and numb & useless (to be fair, her brother was devoured by a zombie in front of her… but damn girl lock in!). Harry is the most overt antagonist of them all.

Harry insists on staying in the cellar rather than joining Ben and the others above ground to fend off zombies. Harry snaps at Ben: “We luck into a safe place and you’re telling us we’ve gotta risk our lives just because somebody might need help?” Selfishness and individualism are weapons of societal subjugation — some will throw others to the wolves (or zombies) if it means they can remain in comfort, or at least what they perceive to be comfort. Some are more comfortable in hiding because it’s scary to be vulnerable.

When Ben’s plan to grab the rescue truck goes sour, he sprints back to the house as zombies feast on Tom and Judy’s charred remains. Harry, however, has locked the farmhouse door and refuses to let Ben in. When Ben breaks down the door and tries to fend off the incoming zombie horde, Harry turns Ben’s rifle onto Ben. Paranoia has poisoned any potential for trust. The zombies are merely the catalyst for arousing the anxieties that kill us and make us kill each other.

One by one, all the humans in the house die or are zombified except for Ben. As the zombie horde breaks into the house, Ben escapes to the cellar and stays there for the night. Come daybreak, an armed small militia arrives near the farmhouse, shooting stray zombies. Ben wakes up to the commotion and arrives upstairs to inspect the scene. He looks through the window, rifle pointed, to inspect the scene.

Then, he is shot. Callously and quickly. The militia then burns him with the zombies. Pictures flash of Ben’s lifeless body dragged and hacked with blades by the white militia. He is then set ablaze.

Though Romero did not intentionally cast a black man as the lead, it feels impossible to divorce the political context of Ben’s fate from race. In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, Romero concedes that the film did become racial in his mind as he learned of Martin Luther King’s assassination on the way to show the film to distributors [13]. The film released only a few months following the assassination.

Ben’s death and the imagery that follows it evokes scenes of white mobs lynching black people they suspect of criminal activity (the criminal activity: blackness). Though Ben spent the film being calculated, compassionate, and determined, his destiny was still set for death. Despite all the effort to evade the zombies’ wrath, it was the cool violence of unknown armed white folk who shot first and asked questions later that led to Ben’s death.

In a 1987 interview with Tim Ferrante, Duane Jones speaks of the racial duplexity in this role:

“We [Duane and extra Betty Ellen Haughey] were driving through downtown Pittsburgh of all places and heading back to Duquesne when all of a sudden we became very aware of the fact that there were some teenagers in a car following us. And at first we thought it was some of the young folks who were around the filming. And I looked back and I said, ‘Betty, those are strangers.’ And then I looked back, one of them started brandishing a tire iron at me. And the paradox and the irony of that I had been walking around brandishing a tire iron at ghouls all day long, and there was somebody brandishing a tire iron at me from a car but in absolute seriousness. And that moment … the total surrealism of the racial nightmare of America being worse than whatever that was we were doing as a metaphor in that film lives with me to this moment [14].”

Zombies both hold the mirror and are the mirror. They prompt you to look at the fears and anxieties that determine human behavior. Sometimes, you become the zombie, a monstrous manifestation of white America’s fears.

In Night of the Living Dead, there is no reason for the zombies behavior; no motive, no controller (a la a bokor), no explanation confirmed by the narrative. 1974 blaxploitation film Sugar Hill flips this script, blending revenge and the supernatural.

Sugar Hill opens in Club Haiti, featuring an eclectic dance performance where screams of pain and pleasure are indistinguishable — it is only till we hear the applause and see the “Club Haiti” sign that the audience realizes this is simply performance. Langston, boyfriend of Diana “Sugar” Hill (Diana played by the electric Marki Bey), is the owner of this club, and white mob boss Morgan wants a piece of that pie. Morgan sends his goonies, three white men and a black man named Fabulous, to beat Langston to death after Langston refuses to give up the club.

After finding Langston dead, Sugar heads to a deteriorating house in the Louisiana bayou, devoid of light and adorned in cobwebs. There, she requests the help of Mama Maitresse. Mama Maitresse asks why Sugar is now a “believer.” Sugar plainly declares her motive: revenge. She then says, “As strong as my love was, my hate is stronger.”

The pair then calls upon Baron Samedi.

Baron curiously comments on Sugar’s unafraid disposition, to which Sugar asserts her lack of fear and her determination to kill Langston’s killers. Baron then awakes his army of the dead, yelling, “All here who have pledged to obey the will of Baron Samedi, slave and master, master and slave, awake!” Zombies break through the Earth, hands outstretched and fingers grasping at air. They have greyish skin, cobwebs strewn over their bodies, and silver marbles where their eyes should be. They wear ghoulish smiles and brandish weapons. They are black and have shackles around their wrists. Baron tells Sugar, “Put them to evil use. It’s all they know or want.”

Sugar Hill firmly places its roots in Haitian Vodou in its exploration of zombie lore. There is explicit reference to Vodou and to the lwa Baron Samedi. The zombies are beings doing the bidding of their bokor (Sugar). And of course, the zombies are black.

The zombies’ shackles implies that they are relics of slavery. When Baron says “evil use” is all the zombies know or want, I first arrive at the realization: these zombies do have thoughts and they do have wants. Rather than being walking empty shells of bygone humans, they are imbued with motivations both internal and from their master. Baron himself says the zombies are both the slave and the master. I pondered the word “evil,” some more, however.

The narrative supports Sugar in her quest for revenge. She defeats the goonies and Morgan, evades law enforcement, and looks damn good while doing it. Though Baron’s words conflate her actions with evil (which, yeah, I guess she is killing people), the audience is still meant to root for Sugar and her zombies. The zombies are karmic justice, even if the actions themselves are not “good.” It pokes fun at the Western view of Vodou and black people’s traditional beliefs as evil.

Then we arrive at: the zombies pursue their own desires of retribution through Sugar’s wishes. In a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it shot, a zombie is removing the shackle on their wrist of their own accord as it rises from the dead. The zombies, through reawakening, have reclaimed some sense of agency. They can now commit vengeance against the white mob goonies (and the tap-dancing Fabulous) that killed Sugar’s man in attempt to usurp Club Haiti, and can achieve a sense of their own retribution while doing so.

Rusty Cundieff’s 1995 anthological horror-comedy, Tales From the Hood, further pushes zombies as their own liberators. The first scary story of Tales From the Hood follows a young black police officer, Clarence Smith.

On Clarence’s first night on the job, he witnesses two white cops apprehend a black man at a traffic stop. Martin Ezekiel Moorehouse is the black man’s name, and he is a city councilman and activist for black rights with a particular passion for eradicating police corruption. The two white cops, Billy Crumfield and Strom Richman beat Moorehouse with their nightsticks. Clarence’s white partner, Newton Hauser, talks Clarence out of reporting Billy and Strom’s behavior. The three officers (Billy, Strom, Newton) feign agreement with Clarence’s request to bring Moorehouse to the hospital. In reality, Billy and Strom frame Moorehouse for heroin use and kill Moorehouse.

The story then flashes forward a year later. Clarence has quit the police force, is ridden with guilt, and drunkenly stumbles in a daze throughout the city. He encounters a mural of Moorehouse and hallucinates a crucified Moorehouse commanding Clarence: bring them to me.

Clarence gathers the three officers to meet him in the cemetary on the anniversary of Moorehouse’s death. When Strom throws a drunken Clarence against the police car and asks why Clarence brought them to the graveyard that night, Clarence responds, “To celebrate!”

When the four arrive at Moorehouse’s grave, Strom pisses on it. Unzipped pants, dirty hands gripping the peen, he pisses on it, and he cackles maniacally. He then urges Billy to do the same while he and Newton draw guns on Clarence. As Billy prepares for peeing, a hand breaks through the earth and grabs Billy’s ballsack.

After a haze of smoke and gunfire, Billy lays dead in an unearthed coffin and Moorehouse stands atop his gravestone. Moorehouse is bug-eyed, bloody, and clutching Billy’s still-beating heart. Welts texture his face and gravelly moans croak from his throat. Moorehouse then pursues Strom and Newton, demonstrating superhuman strength and telekinetic powers. Newton, after being pinned with multiple needles, melts into a mural next to Moorehouse’s. He is painted in red and blue, pinned to a cross and mouth agape in fear. Moorehouse is now no longer relegated to incomprehensible moans. “Welcome to my world,” he jeers. He then grabs Clarence by the throat and snarls, “Where were you when I needed you?”

The zombie in Tales From the Hood is much different from the previously discussed zombies. Moorehouse has goals and ambitions of his own — namely, revenge. He doesn’t follow the orders of others (unlike Clarence, following the cops then following Moorehouse), he commands others to do his bidding. Though he works through Clarence to gather the cops in his grasp, Moorehouse ultimately seals his own revenge and gains his own voice back.

A zombie is a haunting of the past. The dead who were once victims of subjugation and complacency can remind their oppressors of their fighting spirit and determination in liberation.

Still, Tales From the Hood features a rogue individualist tale of liberation through personal vengeance. Only one zombie receives justice. This justice is arguably underpinned by Clarence’s committal to an insane asylum where he is considered guilty for the cop murders. Perhaps this is the nihilistic conclusion of reality, however. It highlights the dangers of being complacent and the consequences of an entire system going unchecked. Individuals are still subject to suffering.

Now: birth, death, blackness, doubles.

These were the main thoughts swirling in my brain’s nebula following my first listen of Tyler, The Creator’s eighth studio album CHROMAKOPIA (2024).

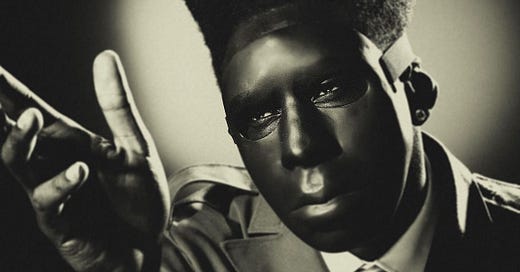

The lens of the zombie seeped through my brain back when the first “ST. CHROMA” teaser dropped. Presumptuous, I know. But stay with me here!

The “ST. CHROMA” teaser. It opens on feet marching, with slightly jilting legs, to a steady heavy beat. It pans upwards to reveal a masked Tyler jerking his torso side to side as he marches on. Then, grunting sounds usher in Tyler’s whispering rap. He straightens up and continues to march, now in perfect aligned form. A high pitched wail floats over the beat. Tyler snaps his head to the right, then back to facing forward. The camera reveals there is a line of other black men marching behind him, falling into form. They are dressed identical to one another and match the swing of his arms and the flick of his head. The sun is bright in the distance behind them, casting a shadow over their features and hiding their faces, an obstruction further aided by the greyscale coloring. Tyler then breaks from the line, still conducting his followers to march on. They march with no sense of their own direction, walk into the CHROMAKOPIA-branded truck, which then explodes. And color is restored.

That’s when the gears in my head began spinning. How can I make this about zombies?

The stench of death was bound to stain this Tyler era after the release of the “SORRY NOT SORRY” music video from his previous (deluxe) album, CALL ME IF YOU GET LOST: The Estate Sale (2023).

In the music video, a shirtless Tyler in black sweatpants (and his natural hair out) brutally murders the “Tylers” donning the styles, hats, and masks synonymous with previous albums. This new Tyler is bloody and drooling.

At the beginning of the video, a man in military attire welcomes the audience to his show. We do not see his face, but we can now recognize the ensemble as evocative of Tyler’s CHROMOKOPIA outfit.

Now back to the “ST. CHROMA” video.

It immediately launches with Tyler’s stumbling as a chorus incants “chromakopia.” Chroma, with its roots in Greek, is defined by Online Etymology Dictionary as “intensity of distinctive hue, degree of departure of a color-sensation from that of white or gray” — other sources translate this as “freedom from white or gray. The Latin suffix “copia” means abundance per the Encyclopedia of Rhetoric.

When the marching figures trapped in the CHROMOKOPIA container explode, color bursts into the screen with intense saturation. With an explosion, the world is liberated from greyscale. There’s a shedding of skin, a rejection of monotony and blindly falling into place. These themes are embedded into the rollout of CHROMAKOPIA itself. Tyler forgoes his personal tradition of dropping a new project every two years. He forgoes embedding a “double feature” in the 10th track on the album. And he released the album on a Monday at 6am.

In the song “St. Chroma,” we hear an additional verse absent from the music video: “I am just a box with the light of thunder in me / Gratitude sits under the hubris that’s on my sleeve … Blowing shit up at home back in Chromakopia.” Here, an explosion represents the release of the passion, desires, and concealed emotions flashing like enclosed lightning.

And let me talk about that damn mask for a second. Mad unsettling. Uncanny, one could say. On my first watch of the video, I couldn’t quite parse the face haphazardly jolting around the screen during the first few seconds. The mask was molded to Tyler’s face, but it didn’t quite look his face. Or any face really. My brain attempted to deconstruct a face beneath the mask. The mask conceals the human underneath, but the viewer still has an inkling that a human is there. This is what it’s like to dissect the zombie, to restore the reanimation of a corpse to the original artifact. Fitting for an album that proves itself to potentially be one of Tyler’s most vulnerable.

CHROMAKOPIA weaves dichotomies and doubles, and this becomes heavily apparent in the second music video released, “NOID.” On this track, Tyler discusses the paranoia that comes with hypervisibility and fame. The video begins once again in a warm-toned greyscale, and Tyler is bug-eyed weaving through a crowd and escaping a tweaking Ayo Edebiri. He sees cars in his rearview mirror that aren’t there. Sees home invaders committing robbery in a wall mirror that aren’t there. A masked Tyler breaks into a barefooted run away from his house, looking over his shoulder and swatting at phantom hands and breath on his back.

Then, a bird’s eye view is assumed and warm hues imbue the screen. Tyler stumbles across the pavement, but something isn’t quite right. His shadows do not match the movements of his body. When above-ground Tyler throws a punch in the air, his shadow warily watches its back. When above-ground Tyler exasperatedly swings his arms back and yells out to the air, the shadow mechanically and coolly raises his arms as if directing a march or sternly knocking an invisible door.

There are two sides to expressed here, and the repressed side that harbors fear, concern, and anxiety is threatening to break loose. The two sides appear more clearly in the lyric graphics he’s posted on various internet platforms. Some songs’ lyric graphics split the lyrics into two columns, with the right column bolder than the left (except for “Darling, I” which does not bold the either side).

The two columns often sing in different perspectives. In “Noid,” the left column expresses a softer, vulnerable fear, with lyrics such as “I want peace but can’t afford ya,” “Triple checking if I locked the door / I know every creak that’s in the floor,” and “I feel them in my shadow.” The narrator seemingly lacks control of the situation. In the right column, a more aggressive tone is assumed: “I don’t wanna take pictures with you niggas or bitches,” “You sing along but you don’t know me,” and “What you want? Leave me alone.” The narrator directly and actively calls out the audience. Similarly, the shadow shots in the “NOID” video display an exchange of control between the shadow and the above-ground Tyler.

The video then ends with a whispered “chromakopia,” different from the self-assured “chromakopia” uttered at the end of the “ST. CHROMA” teaser. The recognition of a wound being opened.

The assertive “chromakopia” returns at the end of the “THOUGHT I WAS DEAD” video, where an unmasked Tyler dances on a wing and talks his shit for one minute and forty-four seconds. It cuts to the masked Tyler inside the plane throughout the video, and color is restored at the very end. A black-and-white toned unmasked Tyler exclaims, “these niggas thought I was dead!” and we switch to a masked Tyler in full saturation, staring at us before turning around.

One other title on CHROMAKOPIA explicitly references death — “I Killed You.” “I Killed You,” is carried by swinging, polyrhythmic drums that are freckled with frenetic synths and guitars and vocals from Santigold. Each line runs until the air can’t be expelled any further, each line punctuated by a gasp and a “bitch, I killed you.” Tyler laments the struggles of embracing black hair: “your natural state is threatening to the point that I point at myself and self-esteem” or “feel ashamed, so we straighten you out” or “I burnt you, I cut you, I filled you up with chemies.” Then, when Tyler comes to the conclusion “talking ’bout my heritage, I could never kill you,” a breath is released. The frenzied energy dissipates and floating harmonies and flutes cushion Tyler calmly urging himself to just “pick that shit out, bitch.”

Tyler admits killing his hair due to shame, but turns around to recognize and fully embrace its beauty. He reinvigorates life into his hair again, with death simply a memory encased in amber to serve as a reminder.

The final track I’d like to touch on, if only briefly, is “Take Your Mask Off.” It’s placed a little past the halfway point of the album and two tracks before “Thought I Was Dead.” Per the accompanying lyric graphic, the song is separated into four. In each section, there is a different subject that Tyler urges to take the mask off, to become one’s true self. By wearing a mask, the subject is repressing the other part of their “double” and rejecting a truth that has been simmering deep inside them. The two selves wish to be reconciled — not shoved down in refusal to stand before a mirror, but to live out loud and freely and with agency and in pure intense color. This is the journey CHROMAKOPIA documents: a metamorphosis from the subordinate, shackled, shell of oneself to a vibrant, living, honest-to-self being.

Through the zombie narrative I’ve crafted, my fear has been replaced with hope.

When I was seven years old, I sat in Sunday School with my left ankle hooked over my right and my hands clasped in front of me. In class, we learned that we shouldn’t be sinners so we can go to heaven and spend an eternity with God where we can be happy forever. Forever, I had thought. Hmm.

We were in training to not fear death; the catechist distilled language into sugar for our child brains to comprehend. “What would you do when you get to heaven?” was the question for the classroom. A question to make us not only prepared but enthusiastic for our eternity, I assumed. An olive branch extended for the paranoia nursing inside me — in vain, of course. I was too hung up on “forever.” And “happy.”

Kids would say what kids say, giggling about their plans to ask God for an Easy-Bake Oven or a one-thousand foot waterslide or ten million hours on the computer or would Jesus let me braid his hair?

But an eternity of happiness frightened me. How could I possibly be happy forever, and then the day after that? At seven years old, three years is damn near half your life. And that was already long as hell. (Damn. I didn’t even try to be normal fr).

I found myself mulling over the concept of eternity and drowning in guilt. In life after death I saw a puppet who only thinks they’re the one pulling the strings. I saw a shell of myself reawakened to life, consciousness in limbo, made to perform “happiness.” I dwelled on how aware I would be of my own post-mortem living, how aware I could be on where the unthinking begins and ends.

Now, I’ve been presented with a zombie as a bruise. Sometimes it’s purple and peeling. Sometimes it looks just like you, except the skin may be a little tougher. A zombie is a bruise on your memory, on your past self, and it comes back to face you with open, oozing tissue begging for healing. Sinews strung taught, it prompts you to ask: who have I become?

The zombie may seem predestined for passivity, but it can harness agency and enter liberation. It can birth color into a new world. After death is cradled like a butterfly in my palms: gentle, feverish, and fluttering. There is power in recognizing your alternate lives and consequently your alternate deaths and being unafraid.

When something unnerves you because it looks like you or because it threatens your perception of your future, this isn’t the time to run. It’s a time to accept the invitation, take your mask off, and reawaken to life. To reunite with yourself absent of fear. Don’t fear the zombie.

REFERENCES

[1] Freud, Sigmund. The Uncanny. 1919.

[2] Johnson, Mikayla. Zombified and Traumatized: Healing in Black Women’s Zombie Literature. 2022. The University of Alabama, MA Thesis.

[3] Effiong, Philip U. “Ginen.” Encyclopedia of African Religion, 2009.

[4] Jionde, Elexus. “A History of Zombies.” YouTube, 15 Oct. 2024.

[5] Younis, Musab. “Race, the World and Time: Haiti, Liberia and Ethiopia (1914–1945).” Millennium: Journal of International Studies, vol. 46, no. 3, 27 May 2018, pp. 352–370, https://doi.org/10.1177/0305829818773088.

[6] Weston, Kelli. “Grave Legacies: The Racialized Origins of the Zombie Myth.” Museum of the Moving Image, https://movingimage.org/feature/white-zombies-nightmares-of-empire/

[7] Rhodes, Gary D. White Zombie: Anatomy of a Horror Film. McFarland & Company Inc, 2001.

[8] Hurston, Zora N. Tell My Horse: Voodoo and Life in Haiti and Jamaica. 1938.

[9] Mafotsing, Line S. T. “How Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti Championed Women’s Rights.” New Lines Magazine, 6 Sept. 2024, https://newlinesmag.com/essays/how-funmilayo-ransome-kuti-championed-womens-rights/

[10] Fela Kuti: Music is the Weapon. Directed by Stephen Tchal-Gadjieff and Jean Jacques Flori, Kino Lorber, 1982.

[11] Effiong, Philip U. “When the zombie becomes critic: Misinterpreting fela’s ‘zombie’ and the need to reexamine his prevailing motifs.” Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, vol. 42, no. 2, 30 June 2021, https://doi.org/10.5070/f742253950.

[12] Waddell, Ketterick. “Dead or Alive: Parables from Black Zombie Media.” Public Parking, 26 Sept. 2023, https://thisispublicparking.com/posts/dead-or-alive-parables-from-black-zombie-media

[13] Couch, Aaron. “George A. Romero on Brad Pitt Killing the Zombie Genre, Why He Avoids Studio Films.” The Hollywood Reporter, 31 Oct. 2016, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/george-a-romero-says-brad-pitt-killed-zombie-genre-942559/

[14] Newby, Richard. “The Lingering Horror of ‘Night of the Living Dead.’” The Hollywood Reporter, 28 Sept. 2018, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/why-night-living-dead-is-more-relevant-ever-1145708/

[15] Sloane, Thomas O. Encyclopedia of Rhetoric, vol. 1. Oxford University Press, 2006.

WOW you ate.